Doug: In their biography of Stan Lee, Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book, authors Jordan Raphael and Tom Spurgeon discuss the "drug issues":

Doug: In their biography of Stan Lee, Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book, authors Jordan Raphael and Tom Spurgeon discuss the "drug issues":Lee wrote the most famous story of this period. In three issues of The Amazing Spider-Man (#'s 96-98, dated May-July 1971), Peter Parker's friend and roommate (and the boyfriend of the ironically named Mary Jane Watson) becomes addicted to tranquilizers. Pillhead Harry Osborn also happens to be the son of arch-villain the Green Goblin, which allows for a few fight scenes amid the domestic drama. The dialogue is sometimes less than convincing, such as Harry's testament to his bad habit in issue #97: "Here it is. This is all I'll need to make me feel on top of the world again." Gil Kane drew the issue with great aplomb and a seriousness that gave the blunt plot a measure of dignity. ...Yet, except for a final conflict where Spider-Man makes the Green Goblin quit fighting by forcing him to confront his hospitalized son, the story lacks the light-hearted self-awareness that originally sold Marvel to its fans. The real world worked much better as a way to undercut fantasy than fantasy worked as a way to shed light on real-world events. Still, all three special Spider-Man issues were a publicity-driven hit, and in the very next issue, Spider-Man was breaking up a prison riot.

Marvel published all three drug-story issues without the Comics Code Authority's stamp of approval, a calculated risk at the time. The CCA was clear that no depictions of drug use would appear in the comic books that received its approval. But Lee, who had been inspired to tackle the issue by a request from officials at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, felt that he and Marvel could win against the code. The story was generally praised by fans and received a rash of positive press coverage. Lee and Marvel won their game of chicken with the CCA. A revised version of the Code, which somewhat better reflected the more media-savvy times of the early 1970's, was issued on the heels of the Spider-Man drug storyline. In September 1972, Lee received a letter from the President's Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention asking for help in coordinating other comic-book efforts in the growing antidrug campaign.

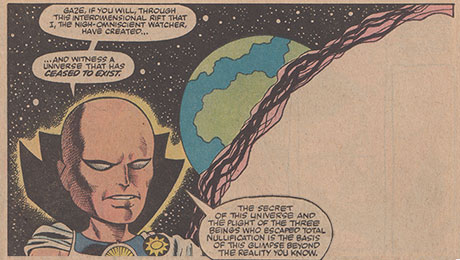

NOTE: The "drug story" that ran in Green Lantern #85, showing a young Roy Harper, aka Speedy (how's that for ironic naming?), using heroin right on the magazine's cover, was cover-dated August/September 1971.

NOTE: The "drug story" that ran in Green Lantern #85, showing a young Roy Harper, aka Speedy (how's that for ironic naming?), using heroin right on the magazine's cover, was cover-dated August/September 1971.

Doug: It's interesting that after the liberalization of social mores in the late 1960's that the Code was forced to re-examine itself. It's even more interesting when we see how the alleged instigator of this censorship had changed his tune. Dr. Frederic Wertham, who most believed ushered in censorship in the comic book industry with the publication of his book Seduction of the Innocent in 1954, told the Miami Herald's Jay Maeder in a 1974 interview: " ...in psychological life, it isn't so that you can say one factor has a clear causal effect on anything. I never said, and I don't think so, that a child reads a comic book and then goes out and beats up his sister or commits a holdup." (quoted from Ron Goulart's Over 50 Years of American Comic Books). Perhaps Wertham's point of view at this time was influenced by the glut of positive press Marvel and DC were receiving in the mainstream American press?

Karen: Or possibly his reaction in the 50s was a product of the times, with all the witch-hunts going on. By 1974, it seems likely he would have mellowed.

Karen: Or possibly his reaction in the 50s was a product of the times, with all the witch-hunts going on. By 1974, it seems likely he would have mellowed.

Doug: So, was Stan a great innovator here, or a risk-taker? Was he going to do it for the social statement, to buck the system, or did he sniff out a slam-dunk sales increase and a national spotlight for this story? One can find several sources that say that while he certainly did go ahead and pull the trigger to run the story, that the national political climate had changed such that, with comic book stories beginning to emulate the new liberalism of the youth culture, it wasn't such a leap that drug-related stories were on the horizon anyway. But then, it was Stan who did it first...

Karen: After reading many interviews with Stan, I honestly believe that his primary motivation was to point out the perils of drug abuse. He has always come across as wanting his comics to send the right message to kids (back when kids actually read comics). Stan was not shy about tackling racial issues either. I'm thinking specifically about the Avengers issues with the Sons of the Serpent, although I think his effort to include African American characters in very positive ways in the books was also a way to subtly combat racism.

Karen: I would say it was more a happy accident that the issues got so much good press. I'm sure Stan was pleased by that, but I don't think his intentions were just about drumming up sales.

Doug: I hope you can read the partial scan of the Stan's Soapbox that ran in Amazing Spider-Man #96, the first of the drug issues. In it, Stan addresses an anonymous critic who, at the top of the column, was taking Marvel to task as a "brainwasher" -- that Marvel comics had begun to deal with social issues such as racism as a way to "pull the wool over our eyes" and "make a fast buck". Now, I was only a mere waif at the time, but I don't think that in the early 1970's showing heroes dealing with racism was trying to whitewash anything -- if nothing else, the Code prohibited comic books from showing the full effect of what was happening in America's schools and on her streets! Here's Stan's reaction, to your right --

Doug: I hope you can read the partial scan of the Stan's Soapbox that ran in Amazing Spider-Man #96, the first of the drug issues. In it, Stan addresses an anonymous critic who, at the top of the column, was taking Marvel to task as a "brainwasher" -- that Marvel comics had begun to deal with social issues such as racism as a way to "pull the wool over our eyes" and "make a fast buck". Now, I was only a mere waif at the time, but I don't think that in the early 1970's showing heroes dealing with racism was trying to whitewash anything -- if nothing else, the Code prohibited comic books from showing the full effect of what was happening in America's schools and on her streets! Here's Stan's reaction, to your right --Doug: I think one thing to remember is that during this time, Stan really did see a lot of the fan mail that came in. And it's well known that it was he who wrote most of the responses in Marvel's various letters columns. So if Stan comments on the pulse of Marveldom Assembled, it was probably not just more hot air from The Man but instead a measure of what their readership really felt about certain stories or issues of the day.

Karen: I recall reading in other interviews with him that they never wanted to alienate any reader, but there were certain things that he felt it was important to take a stance on.

Doug: In closing, let's take a look at how that readership responded to Marvel's decision to go to press without the Comics Code Authority stamp of approval. It is eye-opening to say the least. Now, we of course don't know the ratio of positive fan mail to negative, but I think we can assume that for the most part, in his huckster-ish way, Stan was honest with his readers. I'm going to give him the benefit of the doubt that the letters that were printed on the letters page of Amazing Spider-Man #100 were indicative of the papers that crossed Stan's desk in the days of the fall-out from the publication of Amazing Spider-Man #96.

Karen: I recall reading in other interviews with him that they never wanted to alienate any reader, but there were certain things that he felt it was important to take a stance on.

Doug: In closing, let's take a look at how that readership responded to Marvel's decision to go to press without the Comics Code Authority stamp of approval. It is eye-opening to say the least. Now, we of course don't know the ratio of positive fan mail to negative, but I think we can assume that for the most part, in his huckster-ish way, Stan was honest with his readers. I'm going to give him the benefit of the doubt that the letters that were printed on the letters page of Amazing Spider-Man #100 were indicative of the papers that crossed Stan's desk in the days of the fall-out from the publication of Amazing Spider-Man #96.

No comments:

Post a Comment